The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) is designed to protect and empower individuals who may lack the mental capacity to make their own decisions about their care and treatment and applies to individuals aged 16 and over. . It also allows for people to plan ahead if they think they may lack capacity in the future.

Having mental capacity means being able to understand and retain information and to make a decision based on that information.

However, just because a person has one of these conditions does not necessarily mean they lack the capacity to make a specific decision.

The law aims to ensure that people who lack capacity to make decisions by themselves get the support they need to be as involved as possible in decisions about their lives. It also outlines how an assessment of mental capacity should be made, in which situations other people can make decisions for someone who cannot act on their own and how people can plan ahead in case they become unable to make decisions in the future.

Someone can lack capacity to make some decisions (for example, to decide on complex financial issues) but still have the capacity to make others.

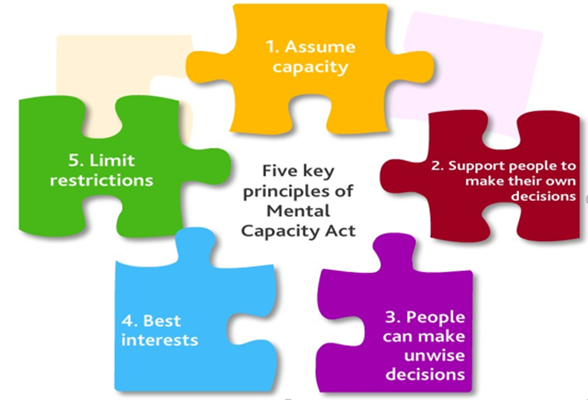

There are five principles at the heart of MCA which should be used to underpin all actions and decisions taken in relation to those who lack capacity:

- Everyone has the right to make their own decisions. Care professionals should always assume an individual is able to make decisions, unless a capacity assessment is carried out and proves otherwise.

- A person must be given help to make a decision. This might include, for example, providing the person with information in a manner that is easier for the individual to understand.

- A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he/she makes what others might see as an unwise decision.

- Where someone is judged not to have the capacity to make specific decisions (following a capacity assessment), that decision can be taken on their behalf, but it must be in the person’s best interests.

- The resulting treatment and care provided should be the least restrictive to the person’s basic rights and freedoms as possible.

The MCA also allows people to express their preferences for treatment and care, as well as allowing the individual to appoint a trusted person (Lasting Power of Attorney) to make the decision on their behalf should the person lack the capacity to make decisions in the future.

The National Mental Capacity Act Competency Framework can be download from Mental Capacity Toolkit - NCPQSW

Find out more about the Legislation by clicking here: Mental Capacity Act

Watch the SCIE Video Resource - About the MCA

Watch the SCIE Video Resource - Overview Using the MCA

When someone lacks mental capacity to consent to care or treatment, it is sometimes necessary to deprive them of their liberty in their best interests, to protect them from harm. The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards are intended to:

- Protect people who lack mental capacity from being detained when this is not in their best interests;

- To prevent arbitrary detention;

- To give people the right to challenge a decision.

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) are part of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The safeguards aim to make sure that people in care homes and hospitals are looked after in a way that does not inappropriately restrict their freedom.

Sometimes the restrictions placed on an individual who lacks the mental capacity to consent to the arrangements for their care may amount to ‘deprivation of liberty’.

Where it appears a deprivation of liberty might have occurred, the provider of care (usually a hospital or care home) has to apply to the local authority, who will then arrange an assessment of the individual’s treatment and care to decide if the deprivation of liberty is in the best interests of the person concerned. Each case must be judged on an individual basis.

If it is in the individual’s best interests, the local authority will grant a legal authorisation. If it is not, the treatment and care package must be changed – otherwise, an unlawful deprivation of liberty will occur. The system is known as the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS).

The DoLS states that deprivation of liberty:

- should be avoided wherever possible;

- should only be authorised in cases where it is in the relevant person’s best interests and the only way to keep them safe;

- should be for as short a time as possible; and

- should be only for a particular treatment plan or course of action.

Arrangements are assessed to check they are necessary and in the person’s best interests. Representation and the right to challenge a deprivation are other safeguards that are part of DoLS.

What constitutes a Deprivation of Liberty?

- Is the individual subject to continuous supervision and control; and

- Is the individual NOT free to leave the placement; and

- Is the individual unable to consent to such arrangements?

If the answer to all of the above questions is ‘Yes’, then the person is deprived of their liberty and authorisation must be sought either via the DoLS Safeguards or via Court of Protection.

A deprivation of liberty that does not have the appropriate authorisation will be unlawful.

If you think someone is being deprived of their liberty without authorisation, contact the DoLS Coordinator for Warrington Adult Social Care 01925 443322

Find out more: Deprivation of Liberty Standards

Independent Mental Capacity Advocacy (IMCA) Service

IMCA’s are an important safeguard for people who lack capacity to make some important decisions. Their role is to help ensure that decisions are reached in the person’s best interests, taking into account their views, wishes, beliefs and values. The IMCA role is to support and represent the person in the decision making process. They do not make decisions on the person’s behalf but do make sure that the Mental Capacity Act is being followed.

IMCA’s are commissioned by the local authority and can only be instructed by local authorities or the NHS. There is no charge to individuals receiving the service.

An IMCA will not usually be needed when someone has family, friends or others who can represent the person, but there will be some exceptions to this.

Power of Attorney

The Mental Capacity Act sets out a range of ways by which people can plan for a time when they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves.

A lasting power of attorney (LPA) is a legal document which allows individuals to give people they trust the authority to manage their affairs if they lack capacity to make certain decisions for themselves in the future.

To set up an LPA a person must be 18 or over, and have the mental capacity to decide to do so. The person the LPA is set up for is known as the donor.

The person chosen to make decision on behalf of the donor is known as the attorney. The attorney must also be over 18 and must themselves have the mental capacity to act as an attorney. For property and financial affairs LPAs, the attorney must not be bankrupt.

A donor can appoint anyone they like as an attorney provided they are an adult with mental capacity, and not bankrupt if appointed for a property and financial affairs LPA. Typically, family members or close friends are chosen. Some people may choose to appoint professionals (for example, solicitors or accountants) to act as their property and finance attorney.

If there is more than one attorney, the donor can decide whether the attorneys must act either:

- ‘jointly’ – which means all decisions must be made together

- ’jointly and severally’- where some decisions have to be made together, but some can be made separately.